2.1 — Hume & Smith the Philosopher

ECON 452 • History of Economic Thought • Fall 2020

Ryan Safner

Assistant Professor of Economics

safner@hood.edu

ryansafner/thoughtF20

thoughtF20.classes.ryansafner.com

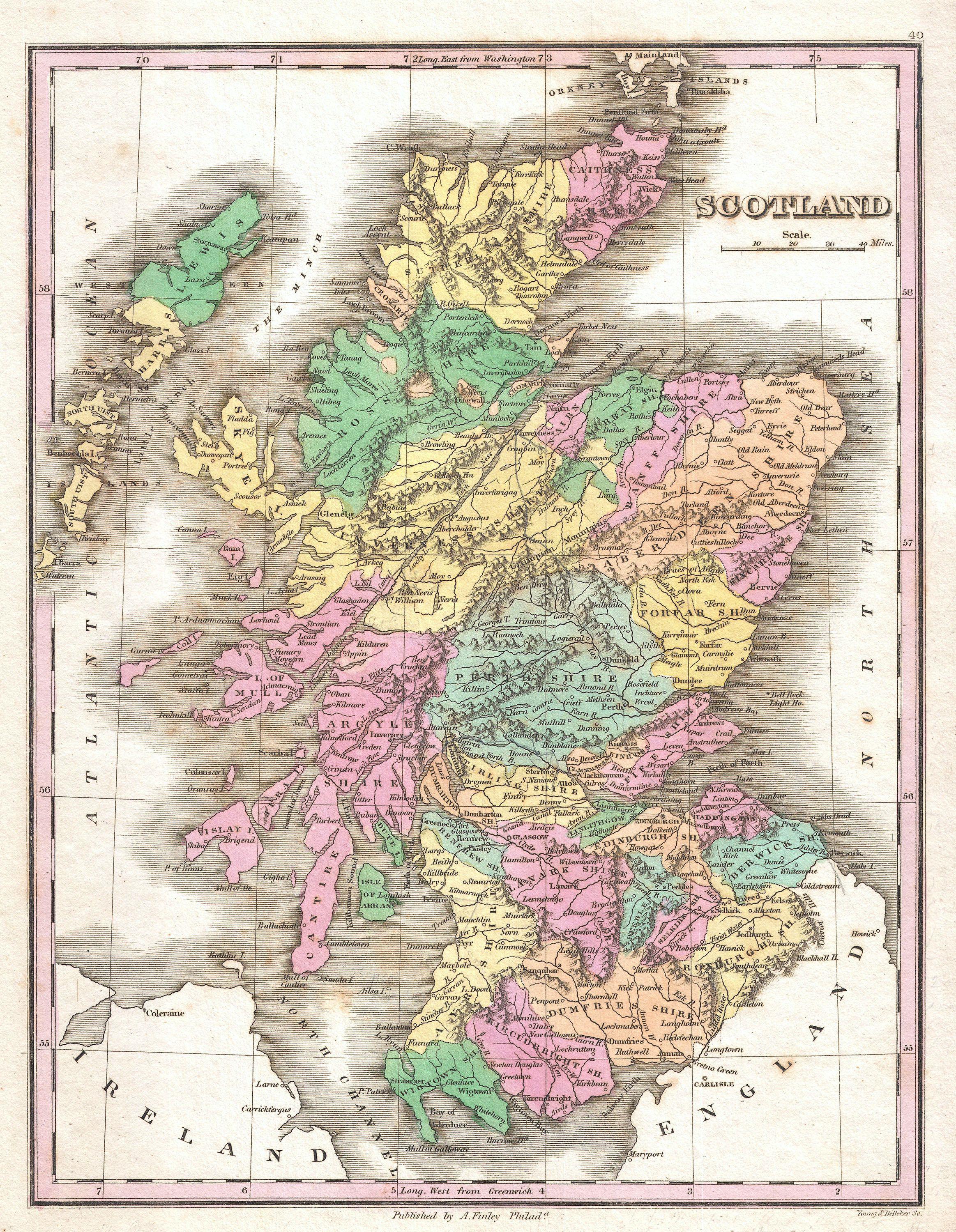

The Scottish Enlightenment

The Scottish Enlightenment

At the turn of the 18th century, Scotland was one of the poorest and most backward corners of Europe

- England about 5x more populous and 36x as wealthy

By the end of the 18th century, Scotland is the center of European science, enlightenment, & commerce

The Scottish Enlightenment

Acts of Union 1707, unite England & Scotland as United Kingdom

The best education system in the world

- Scotland had twice as many universities than England (Edinburgh, Glasgow, Aberdeen, St. Andrews)

- Adam Smith: Oxford & Cambridge had “all but given up the pretense of teaching”

Reformers in the Presbyterian Kirk (Church of Scotland)

- System of formal parish schools

Commercial expansion of trade with American colonies

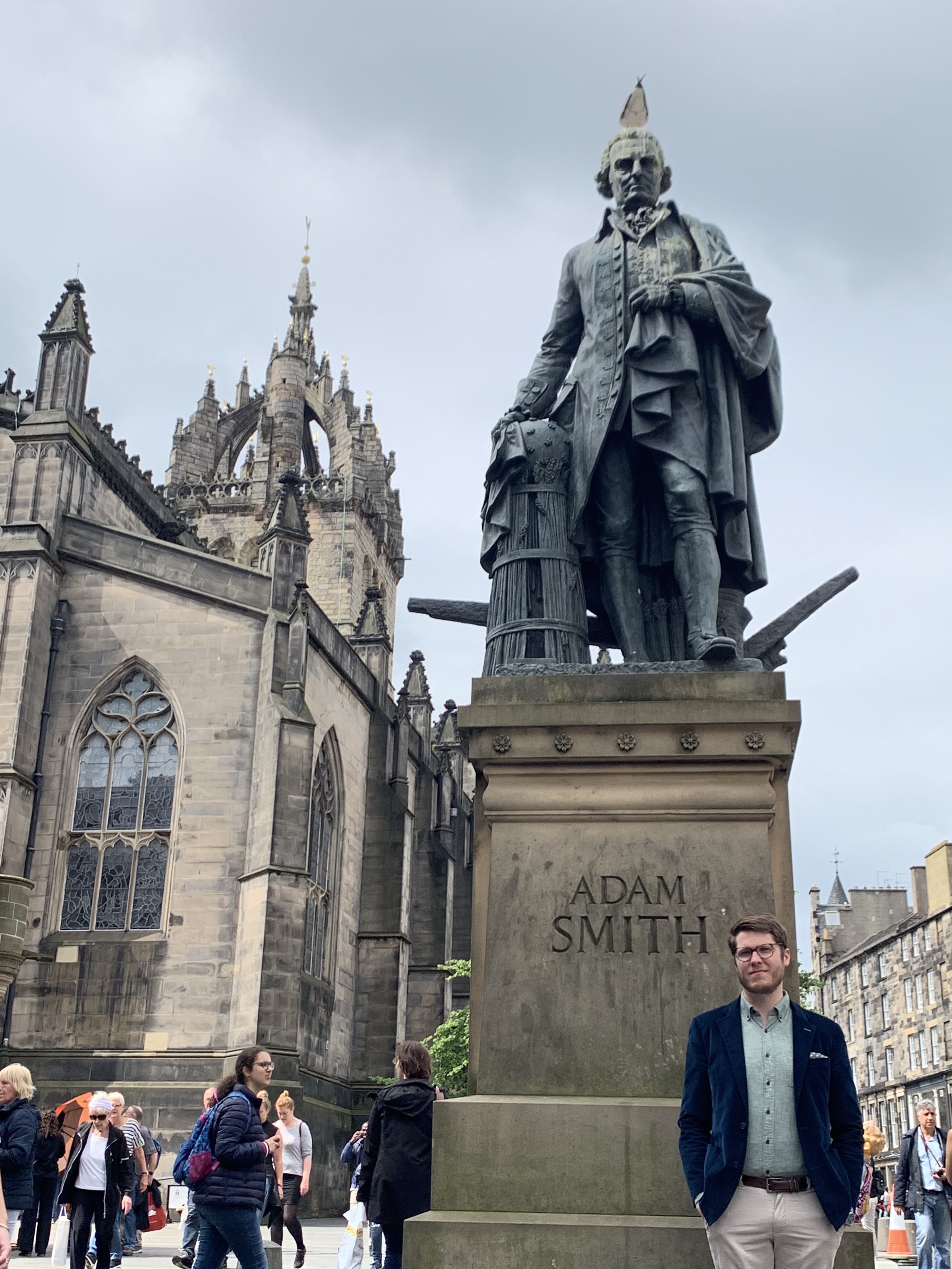

Statutes of David Hume & Adam Smith in Edinburgh

The Scottish Enlightenment: Edinburgh is Awesome

David Hume

David Hume

David Hume

1711-1776

One of the greatest writers in the English language

A giant in the history of thought and enlightenment

- philosophy, morality, science, economics, etc.

1739 A Treatise on Human Nature 1754-1762 The History of England 1741 Essays, Moral, Political, and Literary 1748 An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding 1751 An Enquiry Concerning the Principles of Morals

Hume as The Historian

David Hume

1711-1776

Writes 6 volume The History of England between 1754-1762

- covers from the invasion of Julius Caesar to the Glorious revolution

Viewed the history of England as a gradual quest for liberty emerging out of barbarism & oppression

- England at his writing had “achieved the most entire system of liberty that was ever known amongst mankind”

Widely popular, was the standard history for centuries, made Hume independently wealthy

- intially greeted by outrage by all political factions

- seemingly more Tory than Whig, but evolved over time

- denigrates religion as cause of problems

Hume, David, 1754-1762, The History of England, 6 vols.

Humean Philosophy

David Hume

1711-1776

Hume is one of the greatest empiricists (following Bacon, Hobbes, & Locke)

Human nature and knowledge is derived from experience

Humean Philosophy

David Hume

1711-1776

Epistemology: Hume is one of philosophy's greatest skeptics

- Sharply critical of religion, was an agnostic atheist

- But also critical about the use of pure reason & rationalism

“Reason is, and ought only to be the slave of the passions”

- “Hume's fork”: the distinction between facts (positive) and ideas/values (normative; a priori)

- Our reasoning is motivated by our psychology and interests

Humean Philosophy

David Hume

1711-1776

- Hume's analysis of causality

- We never actually perceive causality, only “constant conjunction” of events

- how do we know with certainty that the sun will rise tomorrow?

"there can be no demonstrative arguments to prove, that those instances, of which we have had no experience, resemble those, of which we have had experience."

Humean Philosophy

David Hume

1711-1776

Defined the problem of induction:

- we can never prove causality or inductive knowledge (in the way deductive reasoning is a priori always true)

- This is what all of the philosophers of science (Popper, Kuhn, etc.) had to answer!

Immanuel Kant: it was Hume who “awoke me from my dogmatic slumbers”

Humean Moral Philosophy

David Hume

1711-1776

- “Hume's guillotine” the is-ought gap

- Separation of positive and normative claims

- Can never prove an ought (normative) from an is (positive)

“In every system of morality, which I have hitherto met with, I have always remarked, that the author proceeds for some time in the ordinary way of reasoning, and establishes the being of a God, or makes observations concerning human affairs; when of a sudden I am surprised to find, that instead of the usual copulations of propositions, is, and is not, I meet with no proposition that is not connected with an ought, or an ought not. This change is imperceptible; but is, however, of the last consequence. For as this ought, or ought not, expresses some new relation or affirmation...the distinction of vice and virtue is not founded merely on the relations of objects, nor is perceived by reason.”

Hume, David, 1739, A Treatise on Human Nature

David Hume: On Morality

David Hume

1711-1776

- Hume is a moral sentimentalist

- moral “truth” does not come from religion or reason, it comes from us

- moral principles come from our emotional responses to experiences and human relationships: “sympathy”

[M]orality is determined by sentiment. It defines virtue to be whatever mental action or quality gives to a spectator the pleasing sentiment of approbation; and vice the contrary.

Hume, David, 1751, Enquiry Concerning the Principles of Morals

David Hume: On Morality

David Hume

1711-1776

Humean sympathy facilitates transfer of emotion from one person to another

- an “emotional contagion”

Our sympathy-based sentiments motivate us towards non-selfish goals, providing for the utility of others

We aim for the approbation of others and avoid the castigation of others

Hume, David, 1751, Enquiry Concerning the Principles of Morals

David Hume: On Morality

David Hume

1711-1776

Morality as disinterested sentiments that correct for personal biases

Must adopt the “general” or “common point of view”

- Consider actions or character traits from a disinterested outside observer with full information

- Dependent on culture, experience, and habit

Smith is also a sentimentalist, adapts & extends Hume

David Hume: On Morality

David Hume

1711-1776

- Contrast and reject “virtues” propounded by religion & moralists:

Celibacy, fasting, penance, mortification, self-denial, humility, silence, solitude, and the whole train of monkish virtues...are...everywhere rejected by men of sense, but because they serve to no manner of purpose; neither advance a man's fortune in the world, nor render him a more valuable member of society; neither qualify him for the entertainment of company, nor increase his power of self-enjoyment? We observe, on the contrary, that they cross all these desirable ends; stupify the understanding and harden the heart, obscure the fancy and sour the temper. We justly, therefore, transfer them to the opposite column, and place them in the catalogue of vices...

Hume, David, 1751, Enquiry Concerning the Principles of Morals

David Hume: On Political Theory

David Hume

1711-1776

“[T]he rules of equity or justice depend entirely on the particular state and condition, in which men are placed, and owe their origin and existence to that UTILITY, which results to the public from their strict and regular observance.

Justifies this by a series of thought experiments (models)

“The common situation of society is a medium amidst all these extremes. We are naturally partial to ourselves, and to our friends; but are capable of learning the advantage resulting from a more equitable conduct. Few enjoyments are given us from the open and liberal hand of nature; but by art, labour, and industry, we can extract them in great abundance. Hence the ideas of property become necessary in all civil society: Hence justice derives its usefulness to the public: And hence alone arises its merit and moral obligation.”

Hume, David, 1751, Enquiry Concerning the Principles of Morals

David Hume: On Political Theory

David Hume

1711-1776

But although men can maintain a small uncultivated society without government, they can’t possibly maintain a society of any kind without justice, i.e. without obeying the three fundamental laws concerning the stability of ownership, its transfer by consent, and the keeping of promises.

Hume, David, 1751, Enquiry Concerning the Principles of Morals

David Hume: On Political Theory

David Hume

1711-1776

Unlike Locke, does not believe that property is a natural right, dependent on the circumstances

Property is justified because of scarcity in the real world

Hume, David, 1751, Enquiry Concerning the Principles of Morals

David Hume: On Political Economy

David Hume

1711-1776

In terms of the history of economic thought, Hume bridges the gap between the mercantilists & the Classical Economists

Demonstrates several fallacies of mercantilism & provides brilliant defenses of free trade

Expands upon Locke's quantity theory of money

David Hume: On Money

David Hume

1711-1776

“Money is not, properly speaking, one of the subjects of commerce; but only the instrument which men have agreed upon to facilitate the exchange of one commodity for another. It is none of the wheels of trade: It is theoilwhich renders the motion of the wheels moresmooth and easy,” (p.135 in Reader)

“If we consider any one kingdom by itself, it is evident, that the greater or less plenty of money is of no consequence; since the prices of commodities are always proportioned to the plenty of money”

Hume, David, 1752, “On Money” in Political Discourses

David Hume: On Money

David Hume

1711-1776

- Probably never read Cantillon, but describes Cantillon effects of money supply increases:

“[I]n every kingdom, into which money begins to flow in greater abundance than formerly, every thing takes a new face: labour and industry gain life...we must consider, that though the high price of commodities be a necessary consequence of the encrease of gold and silver, yet it follows not immediately upon that encrease; but some time is required before the money circulates through the whole state, and makes its effect be felt on all ranks of people...When any quantity of money is imported into a nation, it is not at first dispersed into many hands; but is confined to the coffers of a few persons, who immediately seek to employ it to advantage.”

Hume, David, 1752, “On Money” in Political Discourses

David Hume: On Money and Interest Rates

David Hume

1711-1776

- Attacks the mercantilist & Lockean view that interest rates are determined by money supply

“Were all the gold in England annihilated at once, and one and twenty shillings substituted in the place of every guinea, would money be more plentiful or interest lower? No surely: We should only use silver instead of gold. Were gold rendered as common as silver, and silver as common as copper; would money be more plentiful or interest lower? ... If the multiplying of gold and silver fifteen times makes no difference, much less can the doubling or tripling them. All augmentation has no other effect than to heighten the price of labour and commodities.”

Hume, David, 1752, “Of Interest” in Political Discourses

David Hume: On Money and Interest Rates

David Hume

1711-1776

- Derives his own theory of the origin of interest

“High interest arises from three circumstances: a great demand for borrowing; little riches to supply that demand; and great profits arising from commerce: And these circumstances are a clear proof of the small advance of commerce and industry, not of the scarcity of gold and silver.”

“[S]uppose, that, by miracle, every man in Great Britain should have five pounds slipt into his pocket in one night; this would much more than double the whole money that is at present in the kingdom; yet there would not next day, nor for some time, be any more lenders, nor any variation in the interest”

Hume, David, 1752, “Of Interest” in Political Discourses

David Hume: On International Trade

David Hume

1711-1776

- Explodes mercantilist “balance of trade” doctrine and prohibition of exporting raw materials

“It is very usual, in nations ignorant of the nature of commerce, to prohibit the exportation of commodities, and to preserve among themselves whatever they think valuable and useful. They do not consider, that, in this prohibition, they act directly contrary to their intention; and that the more is exported of any commodity, the more will be raised at home, of which they themselves will always have the first offer,” (p.146 in Reader)

Hume, David, 1752, “Of the Balance of Trade” in Political Discourses

David Hume: On International Trade

David Hume

1711-1776

- Explodes mercantilist “balance of trade” doctrine via his great “price-specie flow mechanism”:

“Suppose four-fifths of all the money in Great Britain be annihilated in one night...what would be the consequence? Must not the price of all labour and commodities sink in proprtion, and everything be sold as cheap? What nation could then dispute with us in any foreign market...which to us would afford sufficient profit? In how little time, therefore, must this bring back the money which we had lost, and raise us to the level of all the neighbouring nations? Where, after we arrived, we immediately lose the advantage of the cheapness of labour and commodities; and the farther flowing in of money is stopped by our fulness and repletion,” (pp.146-147 in Reader)

Hume, David, 1752, “Of the Balance of Trade” in Political Discourses

David Hume: On International Trade

David Hume

1711-1776

- Gives the example inversely to underline the process:

“Again, suppose, that all the money of Great Britain were multiplied fivefold in a night, must not the contrary effect follow? Must not all labour and commodities rise to such an exorbitant height, that no neighbouring nations could afford to buy from us; while their commodities, on the other hand, became comparatively so cheap, that, in spite of all the laws which could be formed, they would be run in upon us, and our money flow out; till we fall to a level with foreigners, and lose that great superiority of riches, which had laid us under such disadvantages?” (p.147 in Reader)

Hume, David, 1752, “Of the Balance of Trade” in Political Discourses

David Hume: On The Virtues of Commerce

David Hume

1711-1776

“[T]he ages of [commercial] refinement are both the happiest and most virtuous...men are kept in perpetual occupation, and enjoy, as their reward, the occupation itself, as well as those pleasures which are the fruit of their labour. The mind acquires new vigour; enlarges its powers and faculties; and by an assiduity in honest industry, both satisfies its natural appetites, and prevents the growth of unnatural ones, which commonly spring up, when nourished by ease and idleness...The same age, which produces great philosophers and politicians, renowned generals and poets, usually abounds with skilful weavers, and ship-carpenters..

Hume, David, 1752, “Of Refinement in the Arts” in Political Discourses

David Hume: On The Virtues of Commerce

David Hume

1711-1776

“The more these refined arts advance, the more sociable men become: nor is it possible, that, when enriched with science, and possessed of a fund of conversation, they should be contented to remain in solitude, or live with their fellow-citizens in that distant manner...They flock into cities; love to receive and communicate knowledge; to show their wit or their breeding; their taste in conversation or living, in clothes or furniture. Curiosity allures the wise; vanity the foolish; and pleasure both...the tempers of men, as well as their behaviour, refine apace. So that, beside the improvements which they receive from knowledge and the liberal arts, it is impossible but they must feel an encrease of humanity, from the very habit of conversing together, and contributing to each other's pleasure and entertainment. Thus industry, knowledge, and humanity, are linked together by an indissoluble chain, and are found, from experience as well as reason, to be peculiar to the more polished, and, what are commonly denominated, the more luxurious ages”

Hume, David, 1752, “Of Refinement in the Arts” in Political Discourses

David Hume: On The Virtues of Commerce

David Hume

1711-1776

“But industry, knowledge, and humanity, are not advantageous in private life alone: They diffuse their beneficial influence on the public, and render the government as great and flourishing as they make individuals happy and prosperous...[A] progress in the arts is rather favourable to liberty, and has a natural tendency to preserve, if not produce a free government”

“In rude unpolished nations, where the arts are neglected, all labour is bestowed on the cultivation of the ground; and the whole society is divided into two classes, proprietors of land, and their vassals or tenants. The latter are necessarily dependent, and fitted for slavery and subjection...The former naturally erect themselves into petty tyrants...they must fall into feuds and contests among themselves...But where luxury nourishes commerce and industry, the peasants,..become rich and independent; while the tradesmen and merchants acquire a share of the property, and draw authority and consideration to that middling rank of men, who are the best and firmest basis of public liberty. These submit not to slavery...They covet equal laws, which may secure their property, and preserve them from monarchical, as well as aristocratical tyranny.”

Hume, David, 1752, “Of Refinement in the Arts” in Political Discourses

Hume & Smith

Adam Smith and David Hume were good friends

Hume, while a famous historian, philosopher, and writer - failed to obtain professorship

- denied @ Glasgow & Edinburgh for his irreligion

Adam Smith gave lectures @ Edinburgh, became professor of moral philosophy at Glasgow

Smith publishes first great book on moral philosophy, The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759)

Today: Smith as moral philosopher; next class: Smith as economist, the Wealth of Nations, and the Classical system

Adam Smith the Philosopher: Theory of Moral Sentiments

Theory of Moral Sentiments

Adam Smith

1723-1790

Critically examines moral theory of his era (sentiments theory of Hume & Smith's teacher Francis Hutcheson)

Goal to explain human capacity for forming moral sentiments

Smithean theory of sympathy: observing behavior and judgments of others allow us to be aware of how others perceive our behavior

- feedback (including imagined) from others (praise or blame) allows us to internalize habits and behaviors to achieve “mutual sympathy of sentiments” with others

Theory of Moral Sentiments

Adam Smith

1723-1790

“As we have no immediate experience of what other men feel, we can form no idea of the manner in which they are affected, but by conceiving what we ourselves should feel in the like situation. Though our brother is on the rack, as long as we ourselves are at our ease, our senses will never inform us of what he suffers. They never did, and never can, carry us beyond our own person, and it is by the imagination only that we can form any conception of what are his sensations...By the imagination, we place ourselves in his situation.”

Smith, Adam, 1759, The Theory of Moral Sentiments

Theory of Moral Sentiments

Adam Smith

1723-1790

- Humans are self-interested by nature, guided by their own needs

“To man is allotted a much humbler department, but one much more suitable to the weakness of his powers, and to the narrowness of his comprehension: the care of his own happiness, of that of his family, his friends, his country...But though we are...endowed with a very strong desire of those ends, it has been entrusted to the slow and uncertain determinations of our reason to find out the proper means of bringing them about. Nature has directed us to the greater part of these by original and immediate instincts. Hunger, thirst, the passion which unites the two sexes, and the dread of pain, prompt us to apply those means for their own sakes, and without any consideration of their tendency to those beneficent ends which the great Director of nature intended to produce by them.”

Smith, Adam, 1759, The Theory of Moral Sentiments

Theory of Moral Sentiments

Adam Smith

1723-1790

- But there is order and harmony in human society because we can sympathize with others

“How selfish soever man may be supposed, there are evidently some principles in his nature, which interest him in the fortune of others, and render their happiness necessary to him, though he derives nothing from it except the pleasure of seeing it.”

“The all-wise Author of Nature has, in this manner, taught man to respect the sentiments and judgments of his brethren; to be more or less pleased when they approve of his conduct, and to be more or less hurt when they disapprove of it. He has made man, if I may say so, the immediate judge of mankind.”

Smith, Adam, 1759, The Theory of Moral Sentiments

Theory of Moral Sentiments

Adam Smith

1723-1790

Critiques (without naming) Hume’s mere ‘mechanical’ version of sympathy as a mere transfer of emotion

- seeing another person angry does not make us angry (unless we learn of what prompted the anger)

Only once we place ourselves in their shoes can we sympathize with their emotion

We can judge whether another’s emotion was warranted by the stimulus

- the propriety or impropriety of others’ actions

Smith, Adam, 1759, The Theory of Moral Sentiments

Smith on Self-Deceit

Adam Smith

1723-1790

- The easiest person to fool is yourself

“This self-deceit, this fatal weakness of mankind, is the source of half the disorders of human life. If we saw ourselves in the light in which others see us, or in which they would see us if they knew all, a reformation would generally be unavoidable. We could not otherwise endure the sight.”

Smith, Adam, 1759, The Theory of Moral Sentiments

Smith on The Impartial Spectator

Adam Smith

1723-1790

- We internalize propriety via the impartial spectator

“We suppose ourselves the spectators of our own behaviour, and endeavour to imagine what effect it would, in this light, produce upon us. This is the only looking glass by which we can, in some measure, with the eyes of other people, scrutinize the propriety of our own conduct.”

“It is from him only that we learn the real littleness of ourselves, and of whatever relates to ourselves, and the natural misrepresentations of self-love can be corrected only by the eye of this impartial spectator. It is he who shows us the propriety of generosity and the deformity of injustice; the propriety of resigning the greatest interests of our own, for the yet greater interests of others...”

Smith, Adam, 1759, The Theory of Moral Sentiments

Smith on The Good Life

Adam Smith

1723-1790

“What so great happiness as to be beloved, and to know that we deserve to be beloved? What so great misery as to be hated, and to know that we deserve to be hated?”

“Man naturally desires, not only to be loved, but to be lovely; or to be that thing which is the natural and proper object of love. He naturally dreads, not only to be hated, but to be hateful; or to be that thing which is the natural and proper object of hatred. He desires, not only praise, but praiseworthiness...he dreads, not only blame, but blameworthiness...”

Smith, Adam, 1759, The Theory of Moral Sentiments

Smith: Happiness ≠ Wealth and Fame

Adam Smith

1723-1790

“In the courts of princes, in the drawing-rooms of the great, where success and preferment depend, not upon the esteem of intelligent and well-informed equals, but upon the fanciful and foolish favour of ignorant, presumptuous, and proud superiors; flattery and falsehood too often prevail over merit and abilities.”

“We frequently see the respectful attentions of the world more strongly directed towards the rich and great, than towards the wise and virtuous.”

“Are you in earnest resolved never to barter your liberty for the lordly servitude of a court, but to live free, fearless, and independent? There seems to be one way to continue in that virtuous resolution...Never enter the place from whence so few have been able to return; never come within the circle of ambition; nor ever bring yourself into comparison with those masters of the earth who have already engrossed the attention of half mankind before you.”

Smith, Adam, 1759, The Theory of Moral Sentiments

Smith: Happiness ≠ Wealth and Fame

Adam Smith

1723-1790

“How many people ruin themselves by laying out money on trinkets of frivolous utility? What pleases these lovers of toys is not so much the utility, as the aptness of the machines are fitted to promote it. All their pockets are stuffed with little conveniencies...They walk about loaded with a multitude of baubles...of which the whole utility is certainly not worth the fatigue of bearing the burden.”

Smith, Adam, 1759, The Theory of Moral Sentiments

Smith: Happiness ≠ Wealth and Fame

Adam Smith

1723-1790

“The poor man's son, whom heaven in its anger has visited with ambition, when he begins to look around him, admires the condition of the rich...and fancies he should be lodged more at his ease in a palace...He sees his superiors carried about in machines, and imagines that in one of these he could travel with less inconveniency...He thinks if he had attained all these, he would sit still contentedly, and be quiet, enjoying himself in the thought of the happiness and tranquillity of his situation. He is enchanted with the distant idea of this felicity. It appears in his fancy like the life of some superior rank of beings, and, in order to arrive at it, he devotes himself for ever to the pursuit of wealth and greatness...With the most unrelenting industry he labours night and day to acquire talents superior to all his competitors...For this purpose he makes his court to all mankind; he serves those whom he hates, and is obsequious to those whom he despises...”

Smith, Adam, 1759, The Theory of Moral Sentiments

Smith: Happiness ≠ Wealth and Fame

Adam Smith

1723-1790

“...Through the whole of his life he pursues the idea of a certain artificial and elegant repose which he may never arrive at, for which he sacrifices a real tranquillity that is at all times in his power, and which, if in the extremity of old age he should at last attain to it, he will find to be in no respect preferable to that humble security and contentment which he had abandoned for it. It is then, in the last dregs of life, his body wasted with toil and diseases, his mind galled and ruffled by the memory of a thousand injuries and disappointments which he imagines he has met with from the injustice of his enemies, or from the perfidy and ingratitude of his friends, that he begins at last to find that wealth and greatness are mere trinkets of frivolous utility, no more adapted for procuring ease of body or tranquility of mind than the tweezer-cases of the lover of toys; and like them too, more troublesome to the person who carries them about with him than all the advantages they can afford him are commodious.”

Smith, Adam, 1759, The Theory of Moral Sentiments

Smith: But Pursuit of Wealth is Socially Useful

Adam Smith

1723-1790

“The pleasures of wealth and greatness, when considered in this complex view, strike the imagination as something grand and beautiful and noble, of which the attainment is well worth all the toil and anxiety which we are so apt to bestow upon it.

“And it is well that nature imposes upon us in this manner. It is this deception which rouses and keeps in continual motion the industry of mankind. It is this which first prompted them to cultivate the ground, to build houses, to found cities and commonwealths, and to invent and improve all the sciences and arts, which ennoble and embellish human life; which have entirely changed the whole face of the globe, have turned the rude forests of nature into agreeable and fertile plains, and made the trackless and barren ocean a new fund of subsistence, and the great high road of communication to the different nations of the earth. The earth by these labours of mankind has been obliged to redouble her natural fertility, and to maintain a greater multitude of inhabitants...They are led by an invisible hand...without intending it, without knowing it, advance the interest of the society, and afford means to the multiplication of the species”

Smith, Adam, 1759, The Theory of Moral Sentiments

Smith: Contra Utopian Political Systems

Adam Smith

1723-1790

The man of system...is apt to be very wise in his own conceit; and is often so enamoured with the supposed beauty of his own ideal plan of government, that he cannot suffer the smallest deviation from any part of it...He seems to imagine that he can arrange the different members of a great society with as much ease as the hand arranges the different pieces upon a chess-board. He does not consider that...in the great chess-board of human society, every single piece has a principle of motion of its own, altogether different from that which the legislature might chuse to impress upon it...If they are opposite or different, the game will go on miserably, and the society must be at all times in the highest degree of disorder,” (Book IV, Ch. II)

Smith, Adam, 1759, The Theory of Moral Sentiments