4.4 — The Keynesian Revolution

ECON 452 • History of Economic Thought • Fall 2020

Ryan Safner

Assistant Professor of Economics

safner@hood.edu

ryansafner/thoughtF20

thoughtF20.classes.ryansafner.com

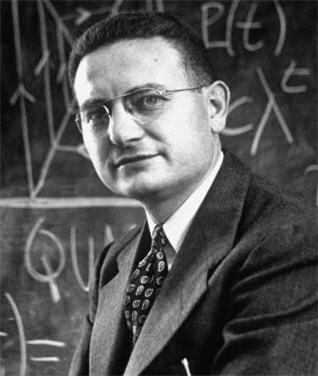

John Maynard Keynes

John Maynard Keynes

John Maynard Keynes

1883-1946

Student of Marshall at Cambridge, trained in mathematics

Earlier work:

- 1919 Economic Consequences of the Peace on The Treaty of Versailles

- 1921 Treatise on Probability

- 1923 Tract on Monetary Reform

- 1930 Treatise on Money

1936 The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money

- sparked the “Keynesian revolution”

- credited with (re?)inventing (modern) “macroeconomics”

- influential in designing post-WWII international system of finance (Bretton-Woods, IMF, WB)

John Maynard Keynes

John Maynard Keynes

1883-1946

A brilliant and eloquent writer

A public intellectual with wide-ranging interests, only a passing flirtation with formal economics, heavily-focused on policy

- Occasional civil servant, never pure academic

Made a fortune in the stock market (from near bankruptcy in 1920 to £2 million by 1946)

John Maynard Keynes

John Maynard Keynes

1883-1946

Keynes died in a car accident in 1946 (62 years old)

Many of the centerpieces of “Keynesian macroeconomics” were developed by his followers (“Neo-Keynesians”) to explain his thought, and make it consistent with neoclassical microeconomics (the neoclassical synthesis)

- Keynesian cross, “paradox of thrift” (Samuelson)

- IS-LM model, “liquidity trap” (Hicks)

- Aggregate demand-aggregate supply model

- National income accounts (Kuznets)

- Econometric models of the macroeconomy

Keynes’ Politics: Anti-Marxist

John Maynard Keynes

1883-1946

“How can I accept a doctrine which sets up as its bible, above and beyond criticism, an obsolete economic textbook which I know to be not only scientifically erroneous, but without interest or application for the modern world? How can I adopt a creed which, preferring the mud to the fish, exalts the boorish proletariat above the bourgeois and the intelligentsia, who, with whatever faults, are the quality in life and surely carry the seeds of all human achievement?”

Keynes, John Maynard, 1932, "A Short View of Russia," Essays in Persuasion

Keynes’ Politics: Pro-Individualism, if not Lassiez-Faire

John Maynard Keynes

1883-1946

“But, above all, individualism, if it can be purged of its defects and its abuses, is the best safeguard of personal liberty in the sense that, compared with any other system, it greatly widens the field for the exercise of personal choice. It is also the best safeguard of the variety of life, which emerges precisely from this extended field of personal choice, and the loss of which is the greatest of all losses of the homogeneous or totalitarian state,” (p.380).

“While, therefore, the enlargement of the functions of government...would seem...to be a terrific encroachment on individualism, I defend it, on the contrary, both as the only practicable means of avoiding the destruction of existing economic forms in their entirety and as the conditions of the successful functioning of individual initiative,” (p.372).

Keynes, John Maynard, 1936, The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money

John Maynard Keynes

John Maynard Keynes

1883-1946

Important to read Keynes in his own words

- Very famous quotes and passages

- Yet hard to put together, many interpretations of Keynes

- Much like Smith or Marshall

A lot of what people consider “Keynesian economics” is not in Keynes!

Next class we will see how various schools of thought interpreted & responded to Keynes

- Neo-Keynesians/neoclassicals (Samuelson, Hicks, Hansen, Lerner, Solow, Tobin)

- Austrians (Mises, Hayek)

- Post-Keynesians (Robinson, Sraffa, Leijonhufvud, Davidson)

- Monetarists (Friedman, Sargent)

- New Classicals (Lucas, Prescott, Kydland, Modigliani, Barro)

- New Keynesians (Mankiw, Krugman, Stiglitz, Akerlof, Summers, Yellen)

Keynes’ Approach to Economics

Keynes’ Approach to Economics

John Maynard Keynes

1883-1946

Does not focus on pure abstract theory

- Universal applicability, simple assumptions

Landreth & Colander: Keynes uses a “realytic” approach

- Contextual blend of observation to make assumptions of the model

- More closely corresponding to policy

- Example: sticky prices & wages without explaining assumption

Keynes, John Maynard, 1936, The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money

Keynes’ Approach to Economics

John Maynard Keynes

1883-1946

Keynes uses only a single diagram, and few equations in The General Theory, almost entirely literary

- All the famous “Keynesian” equations and diagrams (“Keynesian Cross”, IS-LM, etc) came from the Neo-Keynesians (Hicks, Allen, Samuelson, etc) trying to (retro)fit Keynes with neoclassical tools

Famously a badly written, hard to understand, book (very unlike Keynes’ previous works)

- but very quotable — people often quote it without reading it

Keynes, John Maynard, 1936, The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money

Samuelson on Keynes’ General Theory

Paul A. Samuelson

1915-2009

Economics Nobel 1970

“[T]he General Theory...is a badly written book, poorly organized...It abounds in mares’nests and confusions...In it the Keynesian system stands out indistinctly...Flashes of insight and intuition intersperse tedious algebra. An awkward definition suddenly gives way to an unforgettable cadenza. When it is finally mastered, we find its analysis to be obvious and at the same time new. In short, it is a work of genius.”

Keynes On the General Theory

John Maynard Keynes

1883-1946

“I have called this book the General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, placing the emphasis on the prefix general. The object of such a title is to contrast the character of my arguments and conclusions with those of the classical theory of the subject, upon which I was brought up and which dominates the economic thought, both practical and theoretical, of the governing and academic classes of this generation, as it has for a hundred years past. I shall argue that the postulates of the classical theory are applicable to a special case only and not to the general case, the situation which it assumes being a limiting point of the possible positions of equilibrium. Moreover, the characteristics of the special case assumed by the classical theory happen not to be those of the economic society in which we actually live, with the result that its teaching is misleading and disastrous if we attempt to apply it to the facts of experience,” (Chapter 1).

Keynes’ Major Contributions & Claims

John Maynard Keynes

1883-1946

Perhaps his most important claim: markets do not fundamentally guarantee full employment of resources

- denial of Say’s Law

- a focus on aggregate demand deficiencies

- focus on how income

Theory of consumption

- Marginal propensity to consume (income)

- The multiplier

Keynes, John Maynard, 1936, The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money

Keynes’ Major Contributions & Claims

John Maynard Keynes

1883-1946

Theory of money

- Liquidity preference theory of money demand

- inequality of saving and investment

- “animal spirits” and psychology guiding investment

Arguments for fiscal policy

- The multiplier

- Government stimulating aggregate demand

Keynes, John Maynard, 1936, The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money

Keynes Against The Classics and Say’s Law

Keynes Against The Classics and Say’s Law

John Maynard Keynes

1883-1946

“From the time of Say and Ricardo the classical economists have taught that supply creates its own demand; meaning by this in some significant, but not clearly defined, sense that the whole of the costs of production must be spent in the aggregate, directly or indirectly, on purchasing the product,” (p.18).

“[Say’s Law] still underlies the whole classical theory, which would collapse without it.”

Keynes, John Maynard, 1936, The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money

Keynes Against The Classics and Say’s Law

John Maynard Keynes

1883-1946

“The idea that we can safely neglect the aggregate demand function is fundamental to the Ricardian economics, which underlie what we have been taught for more than a century. Malthus, indeed, had vehemently opposed Ricardo’s doctrine that it was impossible for effective demand to be deficient; but vainly. For, since Malthus was unable to explain clearly (apart from an appeal to the facts of common observation) how and why effective demand could be deficient or excessive, he failed to furnish an alternative construction; and Ricardo conquered England as completely as the Holy Inquisition conquered Spain. Not only was his theory accepted by the city, by statesmen and by the academic world. But controversy ceased; the other point of view completely disappeared; it ceased to be discussed. The great puzzle of Effective Demand with which Malthus had wrestled vanished from economic literature. You will not find it mentioned even once in the whole works of Marshall, Edgeworth and Professor Pigou, from whose hands the classical theory has received its most mature embodiment. It could only live on furtively, below the surface, in the underworlds of Karl Marx, Silvio Gesell or Major Douglas.”

Keynes Against The Classics and Say’s Law

John Maynard Keynes

1883-1946

“The completeness of the Ricardian victory is something of a curiosity and a mystery. It must have been due to a complex of suitabilities in the doctrine to the environment into which it was projected. That it reached conclusions quite different from what the ordinary uninstructed person would expect, added, I suppose, to its intellectual prestige. That its teaching, translated into practice, was austere and often unpalatable, lent it virtue. That it was adapted to carry a vast and consistent logical superstructure, gave it beauty. That it could explain much social injustice and apparent cruelty as an inevitable incident in the scheme of progress, and the attempt to change such things as likely on the whole to do more harm than good, commended it to authority. That it afforded a measure of justification to the free activities of the individual capitalist, attracted to it the support of the dominant social force behind authority,”

Keynes Summarizing His Theory

John Maynard Keynes

1883-1946

“The outline of our theory can be expressed as follows. When employment increases aggregate real income is increased. The psychology of the community is such that when aggregate real income is increased aggregate consumption is increased, but not by so much as income. Hence employers would make a loss if the whole of the increased employment were to be devoted to satisfying the increased demand for immediate consumption. Thus, to justify any given amount of employment there must be an amount of current investment sufficient to absorb the excess of total output over what the community chooses to consume when employment is at the given level. For unless there is this amount of investment, the receipts of the entrepreneurs will be less than is required to induce them to offer the given amount of employment. It follows, therefore, that, given what we shall call the community’s propensity to consume, the equilibrium level of employment, i.e. the level at which there is no inducement to employers as a whole either to expand or to contract employment, will depend on the amount of current investment. The amount of current investment will depend, in turn, on what we shall call the inducement to invest; and the inducement to invest will be found to depend on the relation between the schedule of the marginal efficiency of capital and the complex of rates of interest on loans of various maturities and risks.”

Keynes On Nominal Price & Wage Rigidity

John Maynard Keynes

1883-1946

Keynes: The "first postulate of classical economics": "The wage is equal to the marginal product of labour".

Keynes: The "second postulate of classical economics": wage is equal to the disutility of labor

- something that does not change in real terms

- wages often fixed in nominal terms due to wages being fixed by legislation, collective bargaining, or “mere human obstinacy”

Keynes, John Maynard, 1936, The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money

Keynes On Nominal Price & Wage Rigidity

John Maynard Keynes

1883-1946

- Basic idea: prices (especially wages) are rigid, not easily changed

- (Neo)classical economics focuses on how prices adjust to cirumstances to achieve equilibrium

- Keynes: when prices are fixed, quantities adjust to achieve equilibrium, and is is unlikely those equilibrium quantities use all available resources

Keynes, John Maynard, 1936, The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money

Keynes Summarizing His Theory

John Maynard Keynes

1883-1946

“Thus, given the propensity to consume and the rate of new investment, there will be only one level of employment consistent with equilibrium; since any other level will lead to inequality between the aggregate supply price of output as a whole and its aggregate demand price. This level cannot be greater than full employment, i.e. the real wage cannot be less than the marginal disutility of labour. But there is no reason in general for expecting it to be equal to full employment. The effective demand associated with full employment is a special case, only realised when the propensity to consume and the inducement to invest stand in a particular relationship to one another. This particular relationship, which corresponds to the assumptions of the classical theory, is in a sense an optimum relationship. But it can only exist when, by accident or design, current investment provides an amount of demand just equal to the excess of the aggregate supply price of the output resulting from full employment over what the community will choose to spend on consumption when it is fully employed.”

Keynes On Consumption, Saving, and Investment

Keynes On Consumption, Saving, and Investment

John Maynard Keynes

1883-1946

(Neo)classicals: interest rates equilibrate savings & investment

- Smith/Ricardo: a decision to save is a decision to invest/consume but often by different people

Keynes: while saving can equal investment, they are very different decisions driven by different motivations:

- Saving: determined by (psychological?) marginal propensity to consume new income; wealthier save more

- Investment: determined by “marginal efficiency of capital” (return to capital), which is the interest rate

Keynes: income level equilibrates savings & Investment

- equilibrium: money being saved = money invested

- if saving > investment, national income contracts until equilibrated (with less employment)

Keynes, John Maynard, 1936, The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money

Keynes On Consumption, Saving, and Investment

John Maynard Keynes

1883-1946

- Interest is not reward for saving:

“It should be obvious that the rate of interest cannot be a return to saving or waiting as such. For if a man hoards his savings in cash, he earns no interest, though he saves just as much as before. On the contrary, the mere definition of the rate of interest tells us in so many words that the rate of interest is the reward for parting with liquidity for a specified period.” (Ch. 13)

Keynes, John Maynard, 1936, The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money

]

Keynes On Consumption, Saving, and Investment

John Maynard Keynes

1883-1946

People hold money (save) for three reasons: “the transactions motive”, “the precautionary motive”, and “the speculative motive”

For first two motives, demand for money “mainly depends on the level of income”

For the speculative motive: liquidity preference: demand for money is a function of the interest rate alone

- opportunity cost of holding cash is holding interest-earning bonds

“The rate of interest is...the "price" which equilibrates the desire to hold wealth in the form of cash with the available quantity of cash.”

Keynes, John Maynard, 1936, The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money

Keynes on MPC and The Multiplier

John Maynard Keynes

1883-1946

“The fundamental psychological law ... is that men are disposed, as a rule and on average, to increase their consumption as their income increases, but not as much as the increase in their income...”

“Let us define, then, dCdY as the marginal propensity to consume.

“This quantity is of considerable importance, because it tells us how the next increment of output will have to be divided between consumption and investment. For ΔY=ΔC+ΔI, where ΔC and ΔI are the increments of consumption and investment; so that we can write ΔY=kΔI, where 1−1k is equal to the marginal propensity to consume.

“Let us call k the investment multiplier. It tells us that, when there is an increment of aggregate investment, income will increase by an amount which is k times the increment of investment.” (Chapter 10)

Keynes, John Maynard, 1936, The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money

Keynes on The Multiplier

John Maynard Keynes

1883-1946

The multiplier is k=11−MPC, where 1−MPC is the marginal propensity to save MPS

If MPC is 0.9, consumer spends 90% of her income, MPS is 0.10, she saves 10%

Investment in new jobs will create 10x more employment than just the jobs themselves

Keynes, John Maynard, 1936, The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money

Keynes on The Multiplier

John Maynard Keynes

1883-1946

“If the Treasury were to fill old bottles with banknotes, bury them at suitable depths...and leave it to private enterprise...to dig the notes up again...there need be no more unemployment, and...the real income of the community...would probably become a good deal greater than it actually is,” (p.129).

Keynes, John Maynard, 1936, The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money

Dynamics of Keynes’ Theory

Keynes on Uncertainty, Non-ergodicity

John Maynard Keynes

1883-1946

“By ‘uncertain’ knowledge...I do not mean merely to distinguish what is known for certain from what is only probable. The game of roulette is not subject, in this sense, to uncertainty...The sense in which I am using the term is that in which the prospect of a European war is uncertain, or the price of copper and the rate of interest twenty years hence, or the obsolescence of a new invention...About these matters there is no scientific basis on which to form any calculable probability whatever. We simply do not know!” (p.129).

Keynes, John Maynard, 1936, The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money

Keynes on The Role of Expectations

John Maynard Keynes

1883-1946

“The level of employment at any time depends...not merely on the existing state of expectation but on the states of expectation which have existed over a certain past period. Nevertheless past expectations, which have not yet worked themselves out, are embodied in to-day's capital equipment...and only influence [the entrepreneur’s] decisions in so far as they are so embodied,” (Chapter 5)

“The marginal efficiency of capital depends... on current expectations... But, as we have seen, the basis for such expectations is very precarious. Being based on shifting and unreliable evidence, they are subject to sudden and violent changes,” (Chapter 22).

Keynes, John Maynard, 1936, The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money

Keynes on The Role of Expectations

John Maynard Keynes

1883-1946

“Most, probably, of our decisions to do something positive, the full consequences of which will be drawn out over days to come, can only be taken as a result of animal spirits – of a spontaneous urge to action rather than inaction, and not as the outcome of a weighted average of quantified benefits... Thus if the animal spirits are dimmed and spontaneous optimism falters, leaving us to depend on nothing but a mathematical expectation, enterprise will fade and die” (Chapter 12).

Keynes, John Maynard, 1936, The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money

Keynes on The Role of Expectations & Speculation

John Maynard Keynes

1883-1946

“[The stock speculator is concerned] not with what an investment is really worth to a man who buys it ‘for keeps’, but with what the market will value it at, under the influence of mass psychology, three months or a year hence...”

“This battle of wits to anticipate the basis of conventional valuation a few months hence, rather than the prospective yield of an investment over a long term of years, does not even require gulls amongst the public to feed the maws of the professional;– it can be played by professionals amongst themselves. Nor is it necessary that anyone should keep his simple faith in the conventional basis of valuation having any genuine long-term validity. For it is, so to speak, a game of Snap, of Old Maid, of Musical Chairs – a pastime in which he is victor who says Snap neither too soon nor too late, who passed the Old Maid to his neighbour before the game is over, who secures a chair for himself when the music stops.” (Chapter 12).

Keynes, John Maynard, 1936, The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money

Keynes on The Role of Expectations & Speculation

John Maynard Keynes

1883-1946

“[P]rofessional investment may be likened to those newspaper competitions in which the competitors have to pick out the six prettiest faces from a hundred photographs, the prize being awarded to the competitor whose choice most nearly corresponds to the average preferences of the competitors as a whole; so that each competitor has to pick, not those faces which he himself finds prettiest, but those which he thinks likeliest to catch the fancy of the other competitors, all of whom are looking at the problem from the same point of view. It is not a case of choosing those which, to the best of one’s judgment, are really the prettiest, nor even those which average opinion genuinely thinks the prettiest. We have reached the third degree where we devote our intelligences to anticipating what average opinion expects the average opinion to be. And there are some, I believe, who practise the fourth, fifth and higher degrees.” (Chapter 12)

Keynes, John Maynard, 1936, The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money